The results? The majority of test subjects preferred lower pay, as long as those around them earned less. In one famous study, test subjects were asked to choose between two scenarios: earn $100,000 per year with the knowledge that those around them made more, or earn $50,000 per year with the knowledge that those around them made less. Research has found strong ties between our perceived standing among our peers and subjective levels of happiness. However, such comparisons may also lead us to feelings of unhappiness when we see ourselves falling behind our peer group. It may also simply help us feel a sense of belonging within a group.

This comparison can be healthy, as it can help us to evaluate our own progress and standing within a group and inspire us to improve at a particular endeavor or to feel a sense of accomplishment for progress we’ve made. We look at those that we deem to be similar to ourselves and then compare ourselves to this peer group. Research suggests that the most important characteristics for determining our peers are gender and racial/ethnic background, though vocation, geography, and perceived social-economic status also play a role. Social comparison theory, which was first introduced in 1954 by psychologist Leon Festinger, suggests that we have an innate tendency to compare ourselves to those that we consider our peers. But the desire to keep up with the Joneses offers far more complexity than is seen on the surface. We are inherently wired to feel the need to project strength, power, and status to those around us. And though we no longer have to compete for these things in the same way that we once did, our competitive nature remains. Throughout much of our history, humans have had to compete for territory, resources, and mates, among other things, in order to survive and thrive. At our core, humans remain a competitive species. What causes people to feel such an intense need to “keep up with the Joneses?” Research suggests that it comes down to a few important quirks in the human psyche. The Psychology of Keeping Up with the Joneses Research such as this simply confirms what we all know to be true: people have a tendency to compare their lifestyles to those of their peers and then increase their consumption when they feel they might be falling behind. The study showed that this behavior ultimately led to a statistically significant increase in the rate of bankruptcy of non-winners relative to the level seen before the lucky winner’s windfall. Much of this increase in spending was fueled by higher levels of debt and riskier investment behavior on the part of non-winners. One 2018 study by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve found a material increase in household spending in neighborhoods where lottery winners live (excluding spending by the lottery winners themselves).

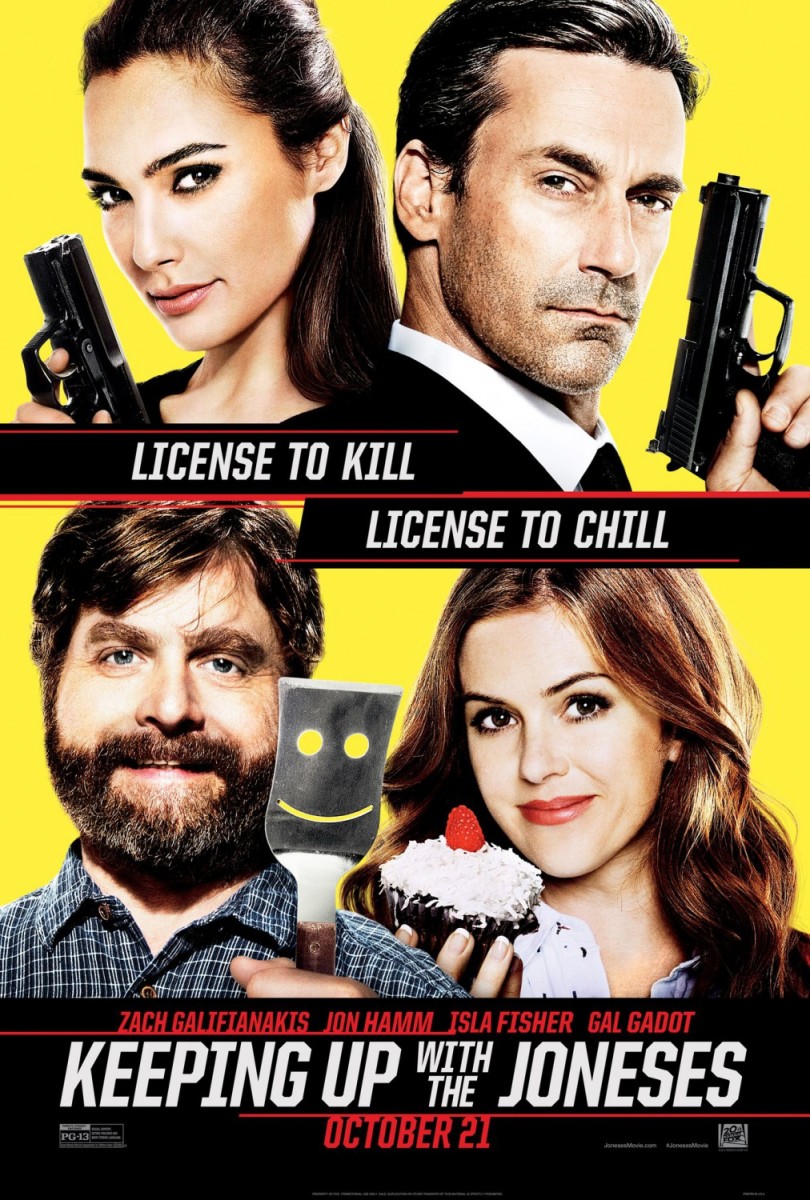

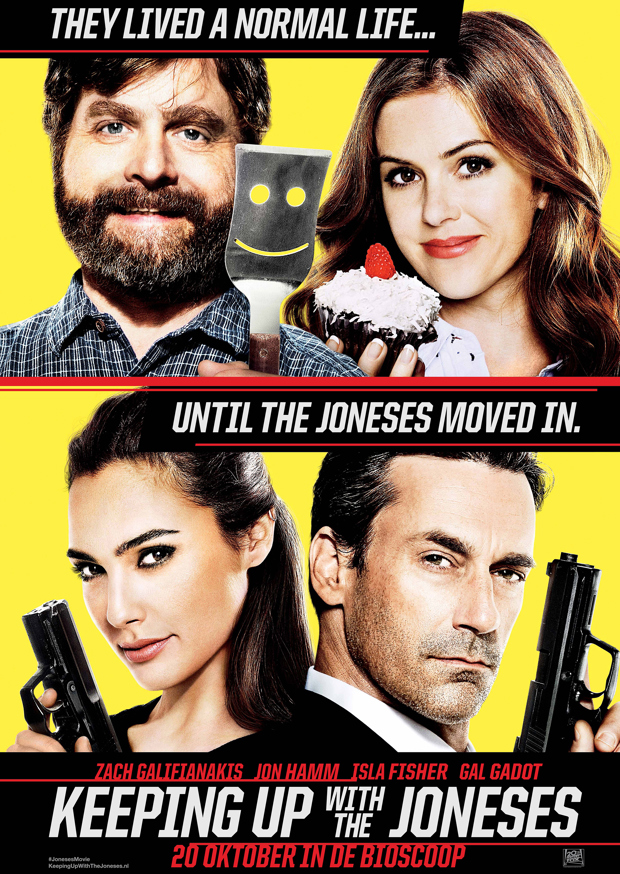

While most of us have anecdotal evidence that the desire to keep up with the Joneses exists, the academic community has also found confirmatory analytical proof of it. The phrase caught on and became a part of common parlance in the United States, where the phenomenon seems to thrive in practically every neighborhood in every town across the land. The author, Arthur Mormand, claimed that the comic strip was based on the experiences of his own family in trying to keep up with the “well-to-do” class in his wealthy Long Island community. The oft-uttered phrase “keeping up with the Joneses” entered the American lexicon in 1913 as the title of a comic strip in which the socially ambitious McGinis family struggles to match the glamorous lifestyle enjoyed by their neighbors, the Joneses. We also discuss some strategies for combatting the all-too-common desire to “keep up with the Joneses.” In this Navigator, we explore the underpinnings of this tendency, as well as the potential adverse consequences that may result from it.

This psychological phenomenon can cause people to excessively expand their lifestyles in order to appear wealthier or financially better off than they really are. The phrase “keeping up with the Joneses” is frequently used to describe the phenomenon of conspicuous consumption by those who are concerned about their relative social standing and prestige.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)